The Hidden Library

There are tunnels beneath the city. Some were built by bootleggers and smugglers, older than anyone now remembers. Damp storage vaults—for hooch and heroin and illegal immigrants from across the ocean—now crumble while traffic rumbles far above. Other tunnels were made later: for the old railway, for the mail system where whirring conveyors once carried stacks from the waterfront station to the main post office.

Dark passageways. Sealed rooms. Silent chambers.

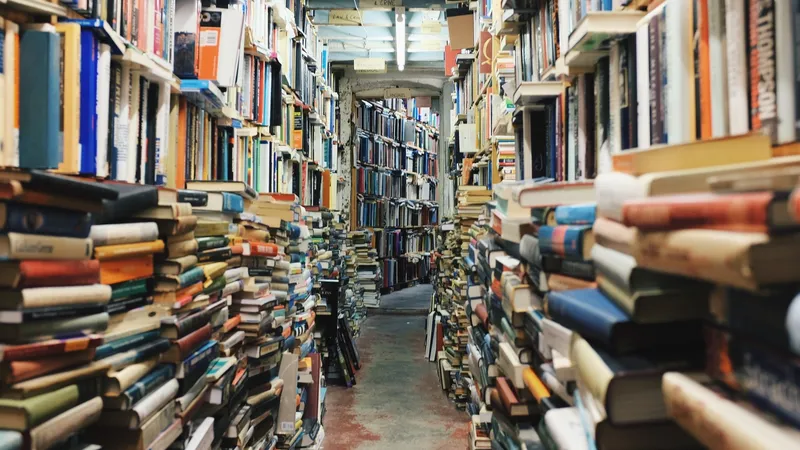

The lost library of Ivan the Terrible is said to lie in hidden tunnels beneath Moscow. The Moscow tunnels descend in stacked levels—six, ten, twelve, who knows?—beneath the modern city. The library, with its countless Byzantine scrolls, is the great and lost treasure of that underground realm. Greek philosophical treatises and ancient Egyptian alchemical texts, chronicles of the rites of ancient religious sects. Geometry and history and mythology wound tight, the light of ideas turned inward and held by vellum and papyrus and copper. All of it kept safe within a library built underground to protect against fire. Hidden away, found (so goes the legend) by Ivan the Terrible, then lost again to history five hundred years ago.

This chapter is about descending. About going down into the tunnels we’ve sealed, the chambers we’ve abandoned, the underground rivers that still flow beneath the structures we’ve built to contain them. It’s about the necessity—in healing from addiction and trauma—of entering the dark places we resist, of recovering the lost library of our own stories, of finding what has been hidden, even from ourselves.

If you are reading this as a parent or loved one, this chapter may be difficult. It asks you to understand that recovery often requires your loved one to go into their pain, not around it. That the healing journey may involve descending into the very experiences they’ve been using substances to avoid. And that you cannot take this journey for them, cannot spare them the descent, cannot fix what lies in their underground.

If you are reading this as someone who recognizes your own sealed tunnels—who knows there are chambers you’ve locked, rivers you’ve dammed, stories you’ve refused to read—then this chapter is for you too. Not as instruction manual, but as acknowledgment that the descent is necessary, and that what waits below includes treasure as well as wound.

Why We Must Descend

Throughout this guide, I’ve explored how addiction emerges from the intersection of developmental vulnerabilities, trauma responses, mental health adaptations, and substance patterns. Each pathway represented a different geography—elsewhere, inward, onward, backward, sideways. But all of these pathways require descent. Whether someone is using hallucinogens to escape presence, opioids to numb unmet needs, stimulants to maintain hypervigilance, alcohol to access rage, or cannabis to avoid everything—the healing journey requires going down into the underground chambers where the original wounding occurred, where the protective pattern first formed, where the unfinished stories wait in darkness.

This descent is not optional. It’s not something we do after stability is achieved, after the substance use has stopped, after the crisis has passed. The descent is the work itself. Without it, we’re simply managing symptoms, rearranging furniture on the surface while the foundation continues to crumble. The tunnels remain, whether we acknowledge them or not. The sealed chambers still contain what was locked away.

From an ecological perspective, descent is necessary for several interconnected reasons.

The system knows what’s down there. The addiction exists because something unbearable was placed in darkness. The substance use, the compulsive behavior—these aren’t random. They’re elegant solutions to impossible developmental dilemmas. The system organized itself around keeping certain experiences sealed away. To change the pattern, we must acknowledge what the pattern is protecting.

Surface interventions create surface changes. When we try to heal addiction without addressing the underground chambers—when we focus only on stopping the substance use, teaching coping skills, or building support networks—we’re working at the wrong scale. These interventions can be valuable, but without descent they create only temporary reorganization. The fundamental pattern remains unchanged.

The wound requires witnessing. Trauma that occurred before language, before memory, before the development of a coherent self—trauma held in the body, in the nervous system, in the implicit patterns of relating—cannot be resolved through cognitive work alone. It requires descent into somatic and implicit experience, into the darkness where these patterns were formed.

The story needs completion. Every addiction carries an unfinished story. The hallucinogen user fleeing from existence that was unwelcome. The opioid user whose needs were never met. The stimulant user who learned the world wasn’t safe to explore. The alcohol user whose will was crushed. These stories don’t have endings—they have infinite repetitions. Descent provides the possibility of witnessing the story completely enough that a new chapter becomes possible.

Why Your Loved One Resists Going Down

Here is something crucial for families to understand: you cannot argue someone into descent. You cannot persuade, convince, or logically demonstrate that they need to face their underground. You cannot drag them into the tunnels, however clearly you see that’s where healing waits.

The resistance to descent is not stubbornness or denial. It’s the nervous system doing exactly what it learned to do: protect against what was once unbearable. The underground contains what the person couldn’t face at the time it happened—experiences so overwhelming that the only survival option was to seal them away. The resistance to opening those seals is not irrational. It’s protective wisdom.

This means that arguments don’t work. Evidence doesn’t work. Pointing out what they’re avoiding doesn’t work. The nervous system doesn’t negotiate verbally. It responds to accumulated experience, to repeated encounters that contradict its predictions about danger. Descent becomes possible not through persuasion but through the gradual building of capacity to bear what was once unbearable.

Your loved one will descend when they’re ready—when they’ve built enough resources, enough support, enough internal capacity. Or they won’t, not yet, and that too deserves respect. Forcing descent before readiness leads not to healing but to retraumatization, to flooding, to collapse that confirms the nervous system’s worst fears about what happens when sealed chambers are opened.

What Waits in the Underground

The tunnels beneath the city form a complex topology—some passages connect, others dead-end, still others loop back to where they began. The topology of each person’s underground is similarly unique, shaped by the specifics of their developmental history, their particular constellation of trauma and resilience.

But there are patterns. Certain features appear consistently in the underground chambers of addicted people.

The original wound lies at the center. This is the event, the relationship, the developmental disruption that created the need for the protective pattern. Often it occurred before explicit memory, sometimes even before birth. Whatever its form, the original wound created an impossible situation—a developmental imperative that couldn’t be met, a need that led to pain, an assertion that brought crushing.

The protective response organized around this wound. The trauma response—flight, freeze, orient, or fight—was brilliant, adaptive, necessary. It kept the developing system intact when integrity was threatened. But it also became rigid, automatic, overdetermined. The protective response that once saved them now imprisons them.

The lost parts wait in darkness. Capacities, qualities, potentials that were split off and sealed away because they were too dangerous to develop. The hallucinogen user’s capacity for presence. The opioid user’s ability to reach out for what they need. The stimulant user’s capacity to be still. The alcohol user’s ability to be powerful without being destructive. These aren’t deficits—they’re parts of self that were placed in darkness for safekeeping.

The unfinished story persists beneath everything. The narrative that got interrupted, frozen mid-sentence, left without resolution. This story continues in the underground, replaying endlessly, seeking completion but finding only repetition. The addiction maintains the story’s incompleteness.

And the hidden resources wait too. The underground isn’t only wound and protection and loss. It also contains treasures. The lost library. Resilience that survived when nothing else could. Imagination that kept possibility alive. Connection to something beyond the wound—call it spirit, soul, purpose—that persisted in the darkness.

When we descend, we’re going down to find all of it. Not just the wound but the wisdom. Not just the trauma but the treasures. The underground contains the complete story, including chapters not yet read.

Personal Testimony: Following the Thread Down

I was raised within the story of alcoholism, within its brooding and volatile atmosphere. I was immersed in that story, and I nurtured it through my teens and early twenties with the false anodyne of socially sanctioned excess. Boys being boys.

I was called away, by my grandmother and other mentors, from that tale of despair. They waited for me at the crossroads, and for a time I passed them by. Yet their voices accompanied me; I heard their echoes from within the valleys of my duress. The slender thread of my connection to their stories—to the possibility of climbing out from my own shadowed tale—was stretched but did not break.

What I learned, finally, is that the descent cannot be avoided. The tunnels call to us. The sealed chambers demand opening. The underground rivers will find their way to the surface, one way or another. We can descend deliberately, with guides and lanterns and the hope of finding treasure. Or we can be dragged down in crisis, in collapse, in the catastrophic flooding that comes when the underground can no longer be contained.

I chose—though it didn’t feel like choice at the time—a long, slow descent. Not a single crisis but a gradual acknowledgment that I needed to go down into the dark. To face the wound of my mother’s alcoholism and my father’s absence. To witness the terror of the adopted child who believed his existence was conditional. To sit with the rage of the crushed will, the grief of unmet needs, the exhaustion of perpetual hypervigilance.

The descent wasn’t linear. I went down, came back up, went down again. I explored different tunnels, found some sealed, discovered unexpected passages. Sometimes I got lost. Sometimes I needed rescue. Always I needed companions—therapists, mentors, my wife who became the guide of all my travels.

What I found in the underground wasn’t only wound and pain. I found parts of myself I’d locked away for safekeeping: imagination, sensitivity, the capacity for wonder. I found the boy who loved books and trees and the sound of rain. I found stories that had been waiting, stories that could provide new chapters to the old tale of alcoholism and abandonment.

The story became more complex, more complete. And in that completeness, healing became possible.

For Parents and Loved Ones: What You Can and Cannot Do

If you’ve read this far, you may be wondering what your role is in your loved one’s descent. You can’t make them go down into their underground. You can’t take the journey for them. You can’t fix what lies in their sealed chambers. What can you do?

You can create conditions that support descent. The therapeutic relationship is central—your loved one needs a guide who can accompany them into the dark. This might be a therapist, counselor, or other professional. Support them in finding this relationship and maintaining it over time. Descent work takes years, not weeks. The person who needs seven years of therapy cannot heal in twelve sessions.

You can provide stability. Descent requires a stable foundation. Basic needs met, crises managed, resources available for bearing intensity. If your loved one is homeless, hungry, or in acute crisis, they cannot do descent work. Help create the conditions of basic safety from which descent becomes possible.

You can offer belonging. Research consistently shows that what heals is belonging—social support, recovery-oriented networks, purposeful contribution to others. Your loved one descends not into isolation but within a web of connection. Family, community, recovery networks, friendships—these provide the relational container that makes descent survivable. The person who knows they will be welcomed when they emerge can risk going down.

You can witness without fixing. When your loved one begins to explore their underground—when old wounds surface, when the story fragments, when emotions emerge that have been sealed for decades—your role is to witness, not to fix. To remain present without flinching, without rushing to make it better, without needing them to be okay so you can be okay. This witnessing is itself healing.

You can respect their timing. Descent cannot be forced. The person will go down when they’re ready, and pushing before readiness leads to retraumatization. If your loved one approaches the threshold and decides the timing isn’t right, the resources aren’t sufficient, the risks are too great—this isn’t failure. This is wisdom. The underground reveals itself in its own time.

You can remember that resistance makes sense. When your loved one pulls back from descent work, when they return to substance use, when they seem to be avoiding the very healing that would help them—remember: they are protecting themselves from what was once unbearable. The resistance is not obstruction; it’s information about what they’re not yet ready to face.

You can tend to yourself. Watching someone you love descend into their darkness is its own kind of journey. You will feel helpless. You will want to rescue them. You will grieve what happened to them, what they’re facing, what cannot be undone. You need your own support—friends, therapists, communities that can hold your experience while you hold space for theirs.

If You Recognize Your Own Sealed Chambers

If you’re reading this and recognizing your own underground—knowing there are tunnels you’ve avoided, chambers you’ve sealed, stories you’ve refused to read—I want to speak to you directly.

The descent is necessary. The tunnels remain whether you acknowledge them or not. The underground rivers will find their way to the surface. You can descend deliberately, with guides and lanterns, or you can be dragged down in crisis. The choice is not whether to face the underground but how.

You cannot do it alone. The descent requires companions—therapists, guides, mentors, communities that can hold what emerges. The container matters as much as the courage. Find a guide you can trust, someone who has done their own descent work, who can accompany you into darkness without flinching.

Building capacity comes first. Before you open sealed chambers, build the resources you’ll need to bear what emerges. Develop affect regulation skills. Establish support networks. Create stability in your external life. The descent requires a foundation of safety from which to venture into unsafe terrain.

The underground contains treasure, not just wound. You’re going down to find all of it—the lost parts of yourself, the resilience that survived, the creativity that was preserved in darkness. The descent is not only suffering. It is also recovery of what was lost.

Resistance deserves respect. If you approach the threshold and decide you’re not ready—that’s information, not failure. The underground reveals itself in its own time. Honor your resistance as protective wisdom while continuing to build the capacity that will make descent possible.

Community supports the work. You don’t descend in isolation. You descend within a web of connection—therapeutic relationships, family, recovery communities, friendships. Finding belonging, finding places where you’re welcomed and valued, provides the relational container that makes the journey survivable. The person who knows they will be received when they emerge can risk going down.

The Threshold

There is a juncture, or a door, or a gate, in all the old tales. On one side lies the known, the practiced, the familiar. And on the far side, unseen and unimagined, lies the Other: the one we left behind, who has been waiting all this time.

In my clinical work, I’ve learned to watch for these threshold moments. They’re rarely dramatic. More often they’re quiet, almost imperceptible—a softening in someone’s voice, a question that suggests readiness, a dream that opens a door. The person who has been running mentions being tired of fleeing. The person who has been frozen expresses a small desire for something beyond relief. The person who has been scanning for danger wonders what stillness might feel like. The person who has been fighting asks tentatively about the cost of perpetual war.

These are threshold moments. The gate is there. The person has found their way to it, though they might not recognize what they’ve found. Our work is not to push them through—that would be violence. Our work is to acknowledge the threshold, to bear witness to the courage it took to arrive here, to offer companionship for whatever comes next.

Sometimes the gate opens. Sometimes it doesn’t, not yet. This isn’t failure. This is wisdom.

The Spring That Cannot Be Stanched

The alcoholic will always be a character in my stories. I will always be cautious of that old tale; its narrative will remain open within me. It flows and will always carry the weight of its passage. Even as I empty it, the spring that is its inexhaustible source will be replenished, and run downstream, and seek the wider waters.

If I do not honor that ancient spring, from which both wounding and wisdom have flowed, if I seek to stanch it, or hide it, or drive off the waters that lie beneath—it might overflow, and sweep me along its path, and drag me under, as it did my mother, until I am drowned.

This is what I want families to understand: the descent doesn’t cure addiction. It doesn’t erase trauma. It doesn’t make the wound disappear. What it does is complete the story enough that new chapters become possible. It integrates what was split off. It brings light to what was hidden. It allows the underground and the surface to be in relationship rather than in opposition.

The tunnels remain. The chambers exist. The underground rivers still flow. But now we know where they are. Now we have maps, however imperfect. Now we can descend deliberately when we need to, rather than waiting to be pulled down by crisis. Now the underground is part of our geography rather than a sealed and terrifying unknown.

When the Descent Doesn’t Lead Where Expected

For some people, the descent doesn’t lead to the transformation this chapter suggests. Some people do the work—years of therapy, careful pacing, skilled accompaniment—and find the addiction unchanged, the wound still raw, the story refusing to complete. The research on trauma therapy shows averages; averages conceal those for whom the treatment failed.

If you have descended and emerged without the transformation you hoped for, you are not doing it wrong. The underground doesn’t yield to everyone equally. Some chambers remain sealed despite our best efforts. Some stories resist completion. This is not failure of will or insufficiency of descent.

It may mean a different approach, a different guide, a different timing. Or it may mean learning to live with what cannot be resolved. Some wounds persist. Some patterns remain. The goal then shifts from transformation to accommodation—finding ways to live meaningfully alongside what cannot be healed, making peace with the underground chambers that refuse to open.

This too is a form of wisdom. This too deserves respect.

For Further Reflection

If You’re a Parent or Loved One

- What do you understand about your loved one’s underground? What wounds might lie there? What protective patterns formed around those wounds?

- How can you support your loved one in finding a guide—a therapist or other professional who can accompany their descent?

- What conditions can you create that support the work? Stability, safety, belonging?

- Can you witness their emerging pain without rushing to fix it? Can you remain present when the underground reveals difficult terrain?

- How do you respect their timing while holding hope for their healing?

- What support do you need as you witness their journey?

If You Recognize Your Own Sealed Chambers

- What tunnels exist in your underground? What chambers have you sealed?

- What capacity do you need to build before descent becomes possible? What resources, what support, what skills?

- Who might serve as guide for your journey? What relationships would provide the container you need?

- Where might you find belonging—community that would hold you through the work, that would welcome you when you emerge?

- What treasures might wait in your underground alongside the wounds? What lost parts of yourself might be waiting there?

- Can you respect your own resistance while continuing to prepare for eventual descent?