The reading project is the first page that you create in the Lab. It is a web page, created and customized by you. The reading project represents your efforts to craft — with text, but also perhaps through images and videos interwoven with the text — a page of content that will be of interest to you (and possibly, eventually, to someone browsing the internet).

In the list below, you will see various examples of writing that embraces hopeful and positive perspectives — especially in the midst of trauma and pain. Each entry includes a short description. Feel free to utilize any of these readings or to choose your own. The important thing is to choose what interests you; reading out of interest is the only valid perspective from which to write something interesting about reading.

Please read in a way that helps you to feel hopeful. Choose readings that emphasize healing, growth, and change. Fittingly, many positive narratives begin in the darkness — in trauma, loss, grief, and death — and move slowly toward discovery, illumination, and joy. How do they get there? Hope points the way.

Feel free to choose one or more books from the list below, or substitute something else. It’s completely up to you. Each book in this list reflects hope in a particular way — usually, as in most powerful storytelling, by reflecting it through sorrow. I have provided short notes about each entry, to offer a sense of context.

You will note that many of the books in this list are from the interconnected genres of science fiction and fantasy. These genres best represent the hopes (and fears) of humanity. Science fiction in particular is a genre of possibilities: what could we change, what might we do, how could we improve the human condition? Hope is always focused on the future; science fiction offers the broadest perspective of what that future might look like and how we might get there. (Science fiction is also the broadest genre in all of literature; it has the breadth to encompass all other genres.)

Possible Readings

Achor, Shawn. The Happiness Advantage

A good overview of positive approaches to health and well-being, from an author who was once a residence advisor at a high-pressure university (Harvard).

Asimov, Isaac. The Robots of Dawn

An old science fiction detective mystery novel that contains the foundational narrative threads of what is considered by many people to be the greatest science fiction series ever written (the Foundation/Robots series). A very hopeful perspective from a robot embodying humanity, exploring “what to do to make things better.” Note, however, that if you choose this book, you really do need to read the other books — 18 in total — to get the full story. (Also note that these books were written between about 1950 and 1990 and reflect perspectives and characterizations that many people would find objectionable today.)

Barker, Eric. Barking Up the Wrong Tree

The subtitle of this book is “The Surprising Science Behind Why Everything You Know About Success Is (Mostly) Wrong.” As with the Shawn Achor book above, Barking up the Wrong Tree is a straightforward exploration of how to cultivate psychological health and well-being.

Bashō, Matsuo. The Narrow Road to the Deep North

Two men travel the backroads of Japan in the late seventeenth century, getting into and out of scrapes with their Zen attitudes and hopeful perspectives intact. Original source of the maxim the journey is the destination.

Butler, Octavia. Parable of the Sower

A science fiction novel about social justice, climate change, religion, and other contemporary topics. Published in 1993 (by Women’s Press); became a New York Times bestseller in the Fall of 2020, during the American election, a time of great anxiety about social justice, climate change, religion, and other contemporary topics.

Dweck, Carol. Mindset.

A foundational book about how your perspective shapes what happens in your life. An academic book (no space battles!) but very interesting. You will be better at math (and perhaps other things) after reading this book.

Jemisin, N.K. The Broken Earth trilogy

Various interesting characters attempt to heal themselves and their shattered world. Written by an author whose first career was as a counsellor. An authentically hopeful post-apocalyptic vision.

Herbert, Frank. The Dune series

A hugely influential science fiction series written in the sixties which includes various mind-bending ideas and themes. Origin of the most famous mantra about facing our fears: the Litany against fear (see below). Also the most famously unfilmable book series of all time (though people keep trying).

King, Stephen. The Dark Tower series

A time-travel romance western sci-fi series, about a band of misfits (and the world's last gunslinger) who attempt to stop the disintegration of the universe. Much emphasis on hope against all odds, finding light in the darkness, and the power of relationships.

Palma, Félix. The Map of Time trilogy

A mystery fantasy historical-fiction time-travel fantasy series, involving interwoven storylines dealing with trauma, grief, loss, and the ways in which personal stories connect to the wider stories of the world (real and imagined). Highly imaginative and hopeful. Originally written in Spanish.

McCullers, Carson. The Heart is a Lonely Hunter

Debut novel of a 23-year-old author who had planned to be a musician but lost all of her tuition money on the subway. The book explores the experiences of misfits and outcasts (and their humanity) in a small town in the state of Georgia. Published in 1940.

Rushdie, Salman. Midnight’s Children

A magic realist story about the beginnings of modern India and the way that personal pathways shape the wider world. If you want an aspirational example of just how good writing can be, this is a book for you. Won the Booker Prize in 1981 as well as the “Booker of Bookers” in 1993 and 2008. Much play, positivity, and wisdom.

Stewart Mary. The Crystal Cave series

You know all those sweeping, romantic fantasy series, the ones with old dragons and young wizards and people falling in love? You’ve maybe read some of those, right? That genre began more than 700 years ago. But its updated, modern versions — the versions in those fantasy and TV series — began with Mary Stewart’s contemporary take on the Arthurian saga in all its glory and hope (sometimes dashed, sometimes redeemed).

Wells, Martha. The Murderbot Diaries series

OK, a series about an android on the run from an evil corporation in a techno-dystopian universe may not sound like a promising narrative for the literature of hope. But it is. Wonderfully so. These books explore what we might do in difficult circumstances, how we might find and support one another, and how we might deepen and discover our humanity (whether we are androids or not). Step one: hack the governor module.

I must not fear. Fear is the mind-killer. Fear is the little-death that brings total obliteration. I will face my fear. I will permit it to pass over me and through me. And when it has gone past, I will turn the inner eye to see its path. Where the fear has gone there will be nothing. Only I will remain.

Possible Viewings

In addition to the reading outlined above, you may wish to view the video series The Inner Life of Stories. In this series, your instructor discusses the interwoven layers of personal development and the relationship between creativity and personal growth.

Details and Possible Content

This project is focused on your responses to the reading you have been doing. What has been interesting to you? What has made you think, or feel? And, since you are a unique person, your responses will be unique to you. There are no right answers or secret criteria here. You are not making an argument in this project, not passing along some version of the main points of what you read. No, you are simply reading, absorbing, reflecting, and then writing. In that order. The essence of what you write about in this project is your reflections on the reading.

I am not asking you to prove that you’ve read anything. Instead – and again, just to make this really clear – I’m asking you to reflect on your reading. Here are some examples of the kinds of things you might reflect upon:

- Why did you choose this particular reading?

- How does this reading make you feel?

- What metaphors or symbols stand out for you, and why?

- Does the reading remind you of something inside yourself? What? And how?

- What does this reading teach you about your life?

- Why do you react to the reading in the way that you do?

- What do these reactions tell you about yourself?

- How might you use the knowledge or insights from your reading to grow as a person or to improve and deepen your relationships with others?

These are just examples. They are not intended to be prescriptive or compulsory. You will learn your own thing, in your own way. But let’s hope that you’ve learned something from your reading. The reading assignment is to write about your reflections (again, in case you missed it the two other times).

Do not write an academic essay! If you do, I will send it back and politely ask you to resubmit the reading assignment. No essays. No five-paragraph boilerplate. No thesis statements. No bibliography. No statements to the effect that you “will demonstrate in this essay”, or that “further, this shows that”, or “in conclusion.” Nope. You have probably learned to write slightly different versions of the exact same essay, over and over again, in your educational journey. If that’s the case, then this assignment will perhaps be anxiety-provoking. I’m asking you to abandon a particular writing skill – traditional essay-writing – and instead try something that might be completely new.

What to write instead of an academic essay? If you’ve been reading a good book, you will have noticed that you don’t see a lot of thesis statements and concluding paragraphs and weasely academic language. Instead, what you see is storytelling. Good writing tells a story – fictional or nonfictional or some strange blend. And the stories we are most drawn to? What do they do? They teach us about ourselves. That’s why we’re drawn to them.

Don’t summarize your reading, or do a book report, or an essay based on what you think I want to hear. This assignment is about you, and your reactions to what you read, and how those reactions percolate around inside you until you know just a bit more about yourself and the world. This is a complex, deep, and somewhat mysterious process that sometimes goes by the name creativity.

This is a straightforward project. And yet, many people struggle with it because I am not telling you exactly what to do. Instead, I am suggesting a direction you might go (reading) and I am encouraging you to follow it wherever it may lead. I don’t know where it will lead; neither do you. In the study of creativity there’s a hifalutin’ word for this process: the liminal space, or liminal zone. Or liminality. The area of uncertainty, ambiguity, and perhaps even disorientation. The place of edges and peering over them.

The description of this assignment is supposed to be vague. That’s the point. All the assignments are going to be like this. It’s your path, your creative journey. You need to follow it (or not) to where it takes you.

How long should it be? Good question. How long do you think? If you spend some time reading, and you learn something really interesting – maybe about yourself, or your relationship with the world – how many words would it take you to write down your reflections about what you’ve learned and what they mean? More than a hundred? For sure. Five hundred? More, probably. More than a thousand? Probably. Ten thousand? Maybe not that much. See how it goes.

I get a lot of assignments that are 1004 words long, or 1002, 1008, or 1033. You get the idea: just over the edge of what I’ve specified as the minimum. Please don’t do that. Write until you’ve reached the point that you’ve said all you need to say. It’s impossible to specify in advance how long that should be – and equally impossible to do it well the night before it’s due. If you rush through this assignment, writing madly at 88 miles per hour to get it submitted before the clock tower signals 10:04 and you’re outta time (you get that pop culture reference, right?), then you will probably not be happy with the result. Instead, take your time. Write this assignment over the course of a week or two, in several shorter writing sessions of maybe an hour each. That should do it.

Storytelling – whether you are writing about your life, or your readings, or the maintenance you do on your motorcycle – is as varied as writers. The more of them that you read (writers as well as stories), the more you will get glimpses of what you could do. It won’t help for me to specify in great detail what the form of your project should be. The more formulaic this project is, the less creative you will be. Your job is to think about how you might create something on your own, and do it. This might be very hard. Try hard – and try not to spend time figuring out what I might want. This assignment is not for me; it’s your creativity, and it’s for you. Remember that if you can.

If you get stuck with this assignment, feel free to reach out to ask questions. But really, getting stuck is part of the process. Getting unstuck is how you activate your creativity.

The reading project is worth 40 percent of your grade and is provisionally due at the end of week 4.

Example Narratives

Writing about reading is a colossal genre with ancient roots. The conversation between readers and writers is one of the most robust and persistent aspects of literature. Sometimes the responses of readers are philosophical and complex (such as Alberto Manguel's response to Walter Benjamin's ruminations on unpacking his library); often they are interwoven with cultural and personal themes (such as Annelie Chen's reflections on Walter Deakin's book about swimming); and sometimes they explore the resonance of personal themes in the writing process (such as Ta-Nehisi Coates' Why I'm Writing Captain America — and why it scares the hell out of me). I don't expect you to craft narratives that are equivalent to these examples, which are written by highly skilled professional authors (Anelise Chen is an accomplished author, essayist, and writing instructor at Columbia University; Alberto Manguel is one of the most renowned and respected authors of our time; and Ta-Nehisi Coates is an influential cultural commentator and author). But we want our aims as writers to be aspirational, right? So, let's take encouragement from the great Arthur Ashe: start where you are, use what you have, do what you can. Read the examples, reflect on what you might do, and go from there.

A Note of Caution

You can write about anything you want. But please consider that any subject that is challenging for you to talk about openly (such as personal trauma) is a subject you should probably not write about — especially on a public platform such as this. On the other hand, powerful personal experiences often provide excellent source material for writing, so it may be difficult for you to decide what to do. First, please use your judgment about how best to keep yourself emotionally safe within and beyond the classroom. Second, please discuss your plans (or your concerns) with me if you decide to write about personal or provocative subjects. In particular, be cautious of subjects involving violence, abuse, trauma, death, mental illness, and related themes (whether they happened to you, happened to someone else, or are imagined). These subjects reliably activate strong emotions and are often unsafe if not handled properly. While no subject is absolutely off-limits in this class, there are many subjects for which there is a risk of harm to you, to me, to others in the class, or to our shared communities. We must be respectful and careful of ourselves and our relationships with others. Please ask me for guidance if you are uncertain.

How to Submit this Project

Create a page. Review this page to see the steps for creating a page.

Add text, images, and perhaps other items (such as videos) to your page. Review the page construction video on this page for how to add text, images, videos, and so on.

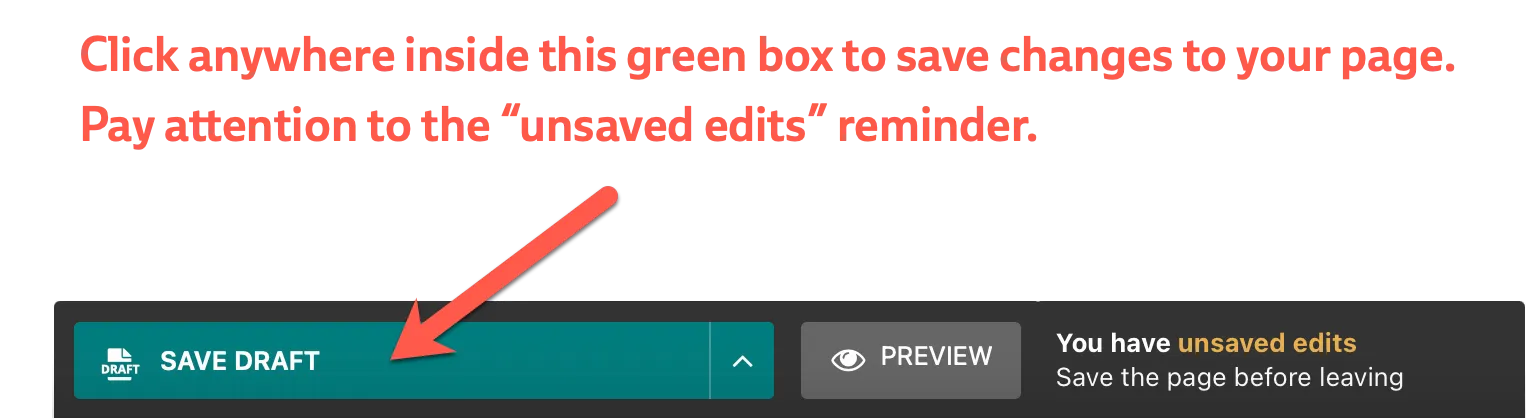

Save the draft of your page. The image below shows the Save Draft button, along with the reminder that appears when you have unsaved edits.

Ask for Feedback (or not; up to you)

Please remember to ask for feedback if you want it. If you do not ask for feedback, you will not receive feedback. (For further details, please review the feedback page.)

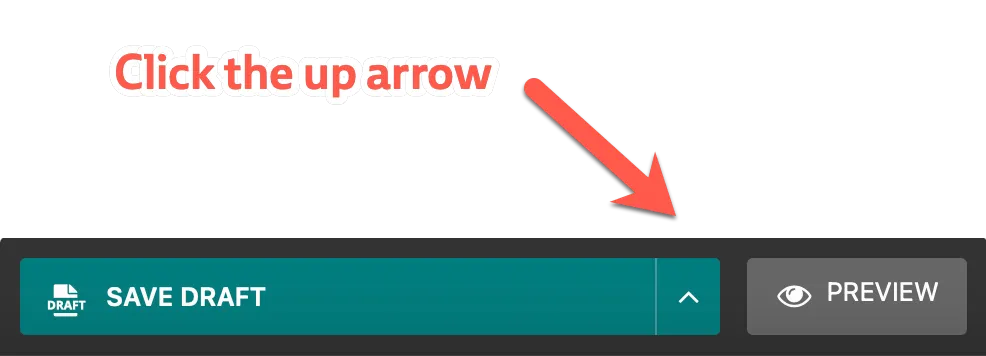

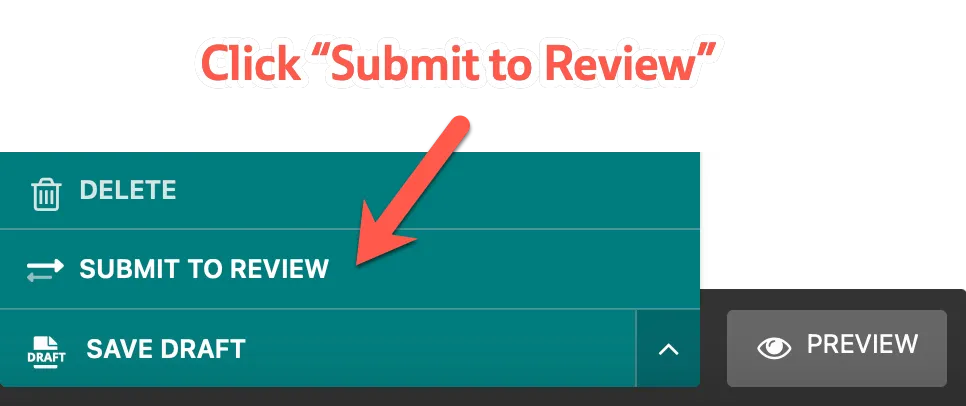

When you are ready to submit your draft for review, click the upward-facing arrow beside Save Draft, then click "Submit to Review". The two images below show this process.

You will receive an email notification that your draft has been submitted to review. The instructor will then review your draft.