The reading project is the first page that you create. It is a web page, created and customized by you. The reading project represents your efforts to craft — with text, but also perhaps through images and videos interwoven with the text — a page of content that will be of interest to you (and possibly, eventually, to someone browsing the internet).

In the list below, you will see various examples of the kind of writing that focuses on bringing the voice of the self out into the world. Each entry includes a short description. Feel free to utilize any of these readings or to choose your own. The important thing is to choose what interests you; reading out of interest is the only valid perspective from which to write something interesting about reading.

Possible Readings

Butala, Sharon. The Perfection of the Morning.

A Canadian author explores the meaning of place while living on a ranch in Saskatchewan.

Butala, Sharon. Wild Stone Heart.

A sequel to The Perfection of the Morning, in which Butala explores the theme of spirituality.

Coates, Ta-Nehisi. Between the World and Me.

A black man writes a letter to his son about the realities of being Black in the United States.

Hackinen, Meaghan. South Away: The Pacific Coast on Two Wheels.

A former student (of your instructor) recounts her cycling adventures.

Hedges, Chris. War Is a Force that Gives Us Meaning.

A war correspondent for the New York Times explores the meaning of trauma and the nature of humanity.

Jerome, John. Stone Work: Reflections on Serious Play and Other Aspects of Country Life.

A man rebuilds an old stone wall on his property while ruminating about creativity, culture, and life.

Matthiessen, Peter. The Snow Leopard.

A man travels to Nepal in search of an elusive animal that becomes a mirror for himself.

Pace, Kristin Knight. This Much Country.

A woman racing her dogsled team in Alsaka discovers that she is really racing herself.

Kingston, Maxine Hong. The Woman Warrior: Memoirs of a Girlhood Among Ghosts.

An Asian woman recounts stories of her early life in China.

Langewiesche, William. Sahara Unveiled: A Journey Across the Desert.

An American travels to Africa to explore the Sahara desert and what it reveals about himself.

Pirsig, Robert. Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance.

A man takes a road trip with his son. The most influential book of writing from the self in all of modern literature.

Saint-Exupéry, A. Wind, Sand and Stars.

The author of The Little Prince recounts his adventures as a professional pilot.

Strayed, Cheryl. Wild.

A woman explores her inner life while hiking the Pacific Crest Trail from California to Washington.

Laird, Ross. Grain of Truth: The Ancient Lessons of Craft.

Your instructor builds things. (Available as an ebook, at no cost to students, via the button below. Also included in Kindle Unlimited.)

Possible Viewings

In addition to the reading outlined above, you may wish to view the video series The Inner Life of Stories. In this series, your instructor discusses the interwoven layers of personal development and the relationship between creativity and personal growth.

Details and Possible Content

This project is focused on your responses to the reading you have been doing. What has been interesting to you? What has made you think, or feel? And, since you are a unique person, your responses will be unique to you. There are no right answers or secret criteria here. You are not making an argument in this project, not passing along some version of the main points of what you read. No, you are simply reading, absorbing, reflecting, and then writing. In that order. The essence of what you write about in this project is your reflections on the reading.

I am not asking you to prove that you’ve read anything. Instead – and again, just to make this really clear – I’m asking you to reflect on your reading. Here are some examples of the kinds of things you might reflect upon:

- Why did you choose this particular reading?

- How does this reading make you feel?

- What metaphors or symbols stand out for you, and why?

- Does the reading remind you of something inside yourself? What? And how?

- What does this reading teach you about your life?

- Why do you react to the reading in the way that you do?

- What do these reactions tell you about yourself?

- How might you use the knowledge or insights from your reading to grow as a person or to improve and deepen your relationships with others?

These are just examples. They are not intended to be prescriptive or compulsory. You will learn your own thing, in your own way. But let’s hope that you’ve learned something from your reading. The reading assignment is to write about your reflections (again, in case you missed it the two other times).

Do not write an academic essay! If you do, I will send it back and politely ask you to resubmit the reading assignment. No essays. No five-paragraph boilerplate. No thesis statements. No bibliography. No statements to the effect that you “will demonstrate in this essay”, or that “further, this shows that”, or “in conclusion.” Nope. You have probably learned to write slightly different versions of the exact same essay, over and over again, in your educational journey. If that’s the case, then this assignment will perhaps be anxiety-provoking. I’m asking you to abandon a particular writing skill – traditional essay-writing – and instead try something that might be completely new.

What to write instead of an academic essay? If you’ve been reading a book (or books) for this class, you will have noticed that you don’t see a lot of thesis statements and concluding paragraphs and weasely academic language. Instead, what you see is storytelling. Good writing tells a story – fictional or nonfictional or some strange blend. And the stories we are most drawn to? What do they do? They teach us about ourselves. That’s why we’re drawn to them.

Don’t summarize your reading, or do a book report, or an essay based on what you think I want to hear. This assignment is about you, and your reactions to what you read, and how those reactions percolate around inside you until you know just a bit more about yourself and the world. This is a complex, deep, and somewhat mysterious process that sometimes goes by the name creativity.

This is a straightforward project. And yet, many people struggle with it because I am not telling you exactly what to do. Instead, I am suggesting a direction you might go (reading) and I am encouraging you to follow it wherever it may lead. I don’t know where it will lead; neither do you. In the study of creativity there’s a hifalutin’ word for this process: the liminal space, or liminal zone. Or liminality. The area of uncertainty, ambiguity, and perhaps even disorientation. The place of edges and peering over them.

The description of this assignment is supposed to be vague. That’s the point. All the assignments are going to be like this. It’s your path, your creative journey. You need to follow it (or not) to where it takes you.

How long should it be? Good question. How long do you think? If you spend some time reading, and you learn something really interesting – maybe about yourself, or your relationship with the world – how many words would it take you to write down your reflections about what you’ve learned and what they mean? More than a hundred? For sure. Five hundred? More, probably. More than a thousand? Probably. Ten thousand? Maybe not that much. See how it goes.

I get a lot of assignments that are 1004 words long, or 1002, 1008, or 1033. You get the idea: just over the edge of what I’ve specified as the minimum. Please don’t do that. Write until you’ve reached the point that you’ve said all you need to say. It’s impossible to specify in advance how long that should be – and equally impossible to do it well the night before it’s due. If you rush through this assignment, writing madly at 88 miles per hour to get it submitted before the clock tower signals 10:04 and you’re outta time (you get that pop culture reference, right?), then you will probably not be happy with the result. Instead, take your time. Write this assignment over the course of a week or two, in several shorter writing sessions of maybe an hour each. That should do it.

Storytelling – whether you are writing about your life, or your readings, or the maintenance you do on your motorcycle – is as varied as writers. The more of them that you read (writers as well as stories), the more you will get glimpses of what you could do. It won’t help for me to specify in great detail what the form of your project should be. The more formulaic this project is, the less creative you will be. Your job is to think about how you might create something on your own, and do it. This might be very hard. Try hard – and try not to spend time figuring out what I might want. This assignment is not for me; it’s your creativity, and it’s for you. Remember that if you can.

If you get stuck with this assignment, feel free to reach out to ask questions. But really, getting stuck is part of the process. Getting unstuck is how you activate your creativity.

The reading project is worth 40 percent of your grade and is provisionally due at the end of week 4.

Example Narratives

Writing about reading is a colossal genre with ancient roots. The conversation between readers and writers is one of the most robust and persistent aspects of literature. Sometimes the responses of readers are philosophical and complex (such as Alberto Manguel's response to Walter Benjamin's ruminations on unpacking his library); often they are interwoven with cultural and personal themes (such as Annelie Chen's reflections on Walter Deakin's book about swimming); and sometimes they explore the resonance of personal themes in the writing process (such as Ta-Nehisi Coates' Why I'm Writing Captain America — and why it scares the hell out of me). I don't expect you to craft narratives that are equivalent to these examples, which are written by highly skilled professional authors (Anelise Chen is an accomplished author, essayist, and writing instructor at Columbia University; Alberto Manguel is one of the most renowned and respected authors of our time; and Ta-Nehisi Coates is an influential cultural commentator and author). But we want our aims as writers to be aspirational, right? So, let's take encouragement from the great Arthur Ashe: start where you are, use what you have, do what you can. Read the examples, reflect on what you might do, and go from there.

A Note of Caution

You can write about anything you want. But please consider that any subject that is challenging for you to talk about openly (such as personal trauma) is a subject you should probably not write about — especially on a public platform such as this. On the other hand, powerful personal experiences often provide excellent source material for writing, so it may be difficult for you to decide what to do. First, please use your judgment about how best to keep yourself emotionally safe within and beyond the classroom. Second, please discuss your plans (or your concerns) with me if you decide to write about personal or provocative subjects. In particular, be cautious of subjects involving violence, abuse, trauma, death, mental illness, and related themes (whether they happened to you, happened to someone else, or are imagined). These subjects reliably activate strong emotions and are often unsafe if not handled properly. While no subject is absolutely off-limits in this class, there are many subjects for which there is a risk of harm to you, to me, to others in the class, or to our shared communities. We must be respectful and careful of ourselves and our relationships with others. Please ask me for guidance if you are uncertain.

How to Submit this Project

Create a page. Review this page to see the steps for creating a page.

Add text, images, and perhaps other items (such as videos) to your page. Review the page construction video on this page for how to add text, images, videos, and so on.

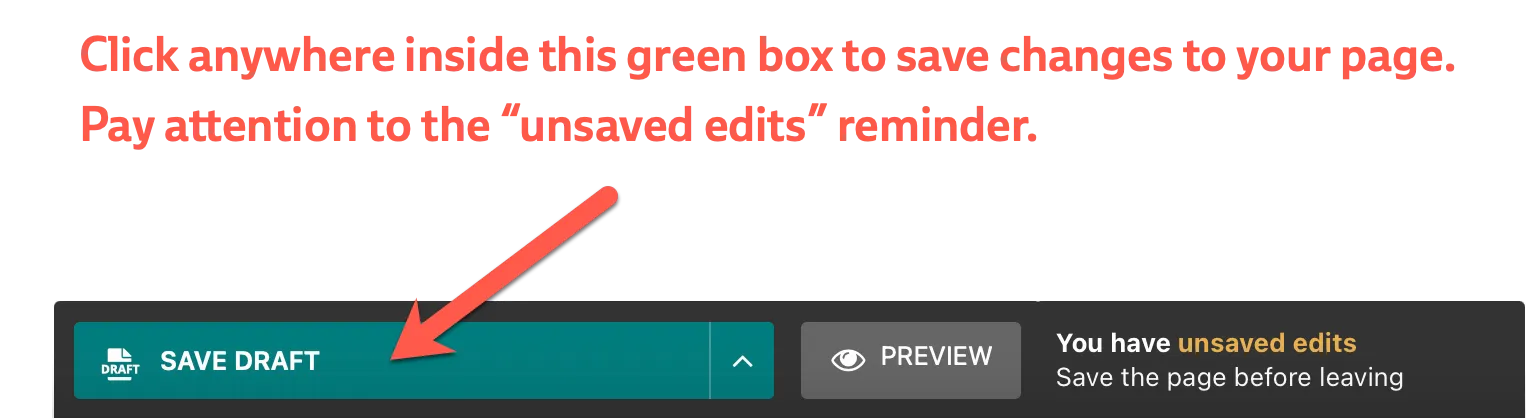

Save the draft of your page. The image below shows the Save Draft button, along with the reminder that appears when you have unsaved edits.

Ask for Feedback (or not)

Please remember to ask for feedback if you want it. If you do not ask for feedback, you will not receive feedback. (For further details, please review the feedback page.)

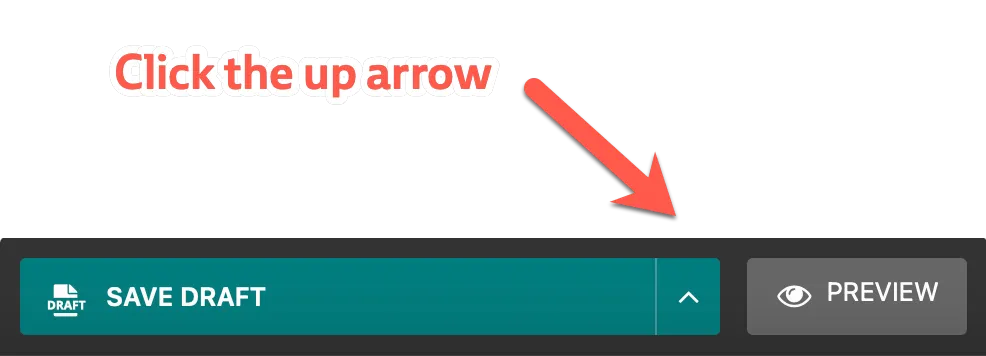

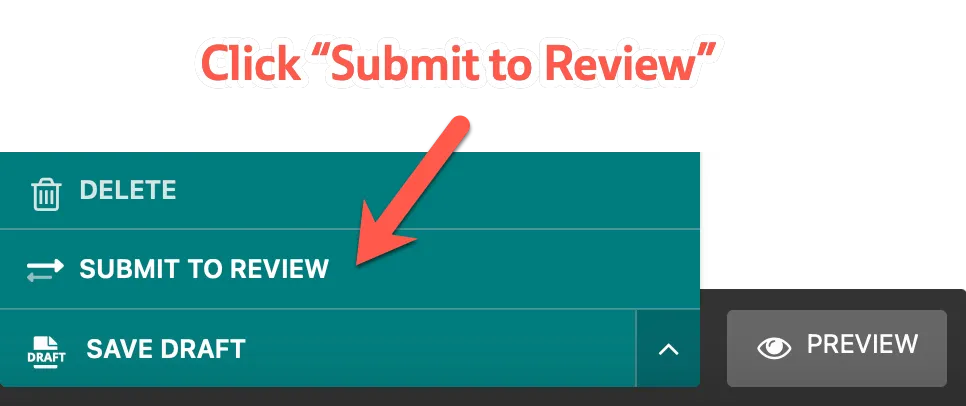

Submit Your Project for Review

When you are ready to submit your draft for review, click the upward-facing arrow beside Save Draft, then click "Submit to Review". The two images below show this process.

You will receive an email notification that your draft has been submitted to review. The instructor will then review your draft.