They were led, one at a time, from the smoky dark of the hold and up the narrow companionway. Each man was flanked by a crew-member who spoke in clipped and rushing tones. The ship was quiet, the sails slack.The men in the hold waited, unsure of what was happening. Dread spread among them. They did not speak the language of the crew, though they understood perfectly the gestures of the guns.

More than two dozen men climbed from the hold into the bright day. The glassy surface of the sea stretched to the horizon on one side, and on the other they saw their destination: hills rising from a rocky shore, a forest tinged with the sea’s blue, white-flecked mountains to the north. Golden Mountain.

The men from the hold were escorted to the foredeck. They saw none of their companions, no other ship, no reason for the threatening behavior of the crew. Fear and bewilderment enclosed them. Some were near panic, others withdrawn. But they all breathed the salt air tinged with the fragrance of earth: damp soil, the sweetness of pine sap, seaweed drying on the beach. As each man stood on the deck,coming alive with the sights and smells of shore, distracted by hope for a few rapt moments, a crewman lifted the hammer and brought it down.

Below, the last men in the hold heard muffled scuffling on deck, quick footsteps, and a series of muted splashes. None of the men with whom they had sailed across the wide ocean, sleeping and talking and fighting in the hold, came back from the deck. The last few became grim, finally understanding what lay ahead for them. But by then it was too late. They were down to a handful of gaunt and weaponless men, malnourished, weakened by a long sea voyage. The hold, suffused with the reek of human confinement, was empty of anything they could use for protection. Their widened eyes were all they could see of each other in the gloom. The men gathered together, and the crew came for them.

But this happens later, at the end, or near enough to it that the ship no longer cares about what happens on its decks. The tale of the Casco does not begin with human cargo, smugglers and pirates. A decade earlier, before its ignoble service at the hands of a mercenary crew, the Casco had been a famous ship of luxury, the last of its kind, traversing the oceans at the close of the age of sail. Even so, the fabled ship has always been associated with tales of pirates, and it is with them that the story properly begins.

In 1881, before Joseph Conrad and Lord Jim, before Joshua Slocum circled the world, before Jack London and The Sea Wolf, Robert Louis Stevenson wrote Treasure Island, the story of a boy coming-of-age among pirates. Stevenson understood the connection between adult sensibilities and childhood dreams more keenly than any other author in English literature. (The year after he completed Treasure Island, he wrote A Child’s Garden of Verses.) He created Long John Silver, and he showed the means by which the innocence of childhood may come to terms with the world’s ruthlessness.

Stevenson would have understood the plight of the men in the Casco’s hold, who had come to find prosperity in the West. After all, Treasure Island sets the dreams of treasure entertained by young Jim Hawkins against Silver’s appetite for murder and piracy. Hidden inside an apple barrel, alone in the dark, unsure of what is to come, Hawkins overhears Silver’s designs for the crew of the Hispaniola: “I give my vote — death. When I’m in Parlyment, and riding in my coach, I don’t want none of these sea-lawyers in the cabin a-coming home, unlooked for, like the devil at prayers.”

The captain of the Casco, a man whose name we do not know, was a smuggler who shared Silver’s sensibilities. A generation after Stevenson wrote Treasure Island, the Casco carried a cargo of thirty-two illegal Chinese immigrants and twenty-pounds of high grade opium — about $800,000 at today’s street value — across the Pacific. An hour from landfall, American customs and revenue authorities saw the familiar rigging of the Casco and pursued her. Though she was fast, the schooner stalled in the deadening wind. From far astern, the revenue cutter kept coming.

The smugglers would have been perplexed to see the bow wave of the cutter undiminished; but they would eventually hear the sound of the steam engine, installed specifically to catch the fugitive Casco. The crew weighed prison against murder. And, as Stevenson would have noted,decency has never been the provenance of pirates.

Stevenson knew the Casco. Twelve years before frightened men huddled in her hold, she had embodied his childhood yearnings for the sea. In 1888,when he was desperately ill with the tuberculosis that had plagued him most of his life, Stevenson leased the Casco for a journey to the South Seas. He hoped that a warm climate might ease his health as well as buoy his spirit. Since early youth, Stevenson had imagined such a voyage, perhaps in the way that young Jim Hawkins had before setting off to seek treasure with Squire Trelawney.

Stevenson, his family, and a small crew left San Francisco in late June. The captain, A.H. Otis, had apparently read Treasure Island but forbade any talk of the book on board, as he found fault with Stevenson’s literary descriptions of seamanship. Stevenson ignored the directive, and later used captain Otis as the model for Arty Nares in The Wrecker: a ‘first-rate navigator and a son of a gun for style.’

The Casco was faster than most ships of her day, and this accounted for a great part of her acclaim. With a main boom of seventy feet, and two masts both close to eighty feet, she was capable of lofting a tremendous amount of canvas. The Casco was also graceful and elegant,but speed was the essence of her appeal — to romantic authors as well as to smugglers. She covered 356 miles in the first twenty-four hours of Stevenson’s voyage to the Marquesas.

Stevenson and his family lived aboard for roughly three months. The author’s health slowly improved, his boyhood dreams of seafaring were fulfilled, and his writing flourished. Four years later, when Stevenson died (of a cerebral hemorrhage, and not of the feared tuberculosis), the red ensign of the Casco was laid across his body.

At Stevenson’s grave in Samoa, the famous epitaph reads:

Here he lies, where he longed to be;

Home is the sailor, home from the sea,

And the hunter home from the hill.

In the South Pacific, the legacy of Stevenson’s sojourn on the Casco is still cherished. In 1988, the Marshall Islands issued commemorative postage stamps of the Casco, which the islanders called the Silver Ship. After Stevenson left her, the schooner kept sailing for another three decades, spending much of her time in Vancouver harbour, slipping ever farther from grace.

The Casco returned from the South Seas and was purchased in 1892 by the Victoria Sealing Company. The mahogany moldings, curtains of blue velvet, and silk bulkhead covers were stripped out. All that remained of her luxurious past was the carved wreath of ivy leaves that surrounded her name upon the bow.

For the next decade, the Casco was the fastest seal ship on the West Coast. Her crew haunted Arctic shores for ten months of the year,then returned home to Victoria, sometimes with more than a thousand skins. During this period the Casco was captained by various men, including (if the old accounts are true), Alex McLean, the model for Larsen, the title character of Jack London’s The Sea Wolf.

But around 1898 the sealing industry was approaching exhaustion, and the Casco was sold again. The record of her ownership and captaincy during the next several years is vague, but the record of her success is legendary. She was possibly the most renowned smuggling ship on the West Coast, traversing the Pacific dozens of times, calling at ports in China, the South Pacific, Japan, Hong Kong — at all the places where underground trade with the Americas flourished.

At first, she was faster than any of the revenue ships. Engines —steam or diesel or gas — had not yet made much headway into the marine trades. All the revenue ships operated, like the Casco, under sail. But the age of sail was coming to a close, and when the revenue authorities installed a steam engine, the Casco’s lead was cancelled.

In or around the fall of 1900, off the southwest coast of Vancouver Island, as the Casco was heading ashore with its human cargo and opium, the wind died and the revenue cutter closed under power from far astern. The crew of the Casco was desperate. They met on deck, as had Long John Silver and the other pirates of Stevenson’s imagination, and settled on the course of murder. Before the revenue ship came close enough to see what was happening, the Casco’s crew brought the immigrants up on deck, one by one, struck them on the back of the head, weighted the bodies with coal, and threw them overboard. The opium went too.

The authorities came aboard, and nothing was found. The captain of the Casco shrugged, feigned umbrage at the intrusion, and the Casco sailed on. But over the next few months, in Victoria and Vancouver and San Francisco, snippets of the tale were heard in taverns and on wharves. The crew of the Casco discovered that some secrets are too difficult to keep.

No charges were ever laid. There was no evidence, no crew member willing to come forward; nothing but the unreliable tales of old seafarers.

The Casco continued sailing, changing hands several more times, eventually making her way to Vancouver, where she was moored west of what is now Canada Place. Her owner sent her for repairs and reconfiguration (for the fishing trade, and possibly for more smuggling) at the original Vancouver Shipyards. Tradesmen working for William Watts found three cut glass bottles hidden in the ship’s timbers. One bottle has since broken, but a wine and water bottle are still prized by the family. Jack Watts, the grandson of William Watts, believes the bottles may have been hidden by Stevenson himself, stowaways from an age of pirates and cherished sea tales.

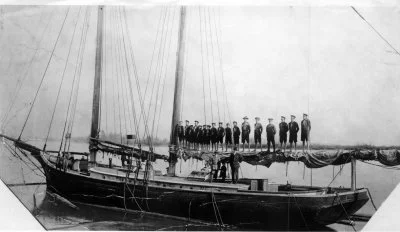

In 1913 and 1914, while she lay unused in Vancouver Harbour, the first troop of Vancouver Sea Scouts secured the right to use the Casco as a training vessel. A few old-timers still remember the dark, sleek hull, and the boys who used to balance on her long boom. The Scouts kept their gear tied neatly at the base of the mainmast. Most were aware of Stevenson’s connection to the ship, but none knew of its other, more disturbing legacy.

The Casco weathered the war as a supply ship, then was sold again, in 1919, to a group of investors looking for Siberian gold. The captain, C.L. Oliver, had never been to sea before, and of the twenty-nine crew, only two were seasoned sailors. One of their number, Kenneth Leuty, kept a diary of the voyage in which he spoke of violence and recklessness on board. In the late summer of 1919, as the Casco sailed ever northward toward the ice of the Bering Sea, Leuty wrote: “I have thought things over and decided to get back to Nome, as the bunch are about crazy. They want to winter in the ice, and I know what that means. The skipper does not know the first thing about sailing, and when he gets into the ice he’s done.”

Leuty was right. He left the Casco when it met another ship, and he slowly made his way home. Ironically, the ship to which he transferred, the Belvedere, was itself wrecked by ice and Leuty, along with the Belvedere’s crew, had to be rescued.

The Casco kept sailing north, into the far reaches of the Siberian coast, but in early September she was pressed south and east by storms and early ice. The captain turned the helm toward Alaska. On September 9 she met a gale from the southeast that drove her into the ice near King Island. Although the teak hull was fractured, the crew made it to shore. Within minutes, the Casco was gone.

With her demise, it seemed that the tale of the murdered immigrants disappeared as well. For thirty years, nothing more was heard of the incident. The Casco came increasingly to be identified with Stevenson only, and the schooner is now remembered with fondness by many sailors who harbour literary tastes.

But in the early 1950’s, a BC writer named Francis Dickie claimed to have met, in a ‘grimy waterfront tavern’ in Victoria, an old sailor who told a strange tale. The seafarer’s tavern as a place of sheltered secrets is almost archetypal: Treasure Island begins at the Admiral Benbow Inn, moves to the Spy-Glass tavern in Bristol, and only departs to sea once the narrative has been firmly established at dockside. Almost a third of Treasure Island takes place in taverns.

Dickie plied the sailor with cheap beer, and they spoke of the Casco. Apparently the man had been a member of the crew around 1900, and was aboard when the wind failed and the revenue cutter did not slow in its approach. He confirmed what had been long rumoured: the immigrants, the opium, the desperate brutality of it all. The sailor remembered that the body of the last man was weighted with the last of the ship’s coal.

Today, no one knows if the tale is true. The details are now more than a century old, the crew is gone, nothing remains of the ship. But the tale persists, in maritime museums, in nautical books, in old memories. The Casco still carries her cargo of fables and ghosts.

In Chinese mythology and spirituality, ghosts inhabit the twilight. Theirs is the territory between the living and the dead, between the impulse and the completed act. They are not yet done with the world. The Chinese men who sought North America — their Golden Mountain — did not complete the voyage. They did not find their Treasure Island, nor claim a share of the bounty to be found here. They were lost.

But Stevenson would have said that a story could redeem them from the storm of ghosts. He would have delivered them, out of the path of pirates, and brought them to a new home: where they longed to be, home is the sailor, home from the sea.